In 2014, the South Carolina Department of Transportation (SCDOT) established a new team to focus exclusively on an accelerated construction project delivery method known as Design-Build. The team would be responsible for around five large projects a year, as well as three multi-bridge package projects and any emergency projects.

In a traditional construction project, a general contractor will bid on a project after a predetermined architect or designer has already completed its drawings. Construction begins after the bid is awarded. This delivery method, known as Design-Bid-Build, is effective but not maximally efficient.

“It’s essentially like a relay race, where the baton is passed from the designer to the contractor,” said Brooks Bickley, an assistant program manager with SCDOT who oversaw the Design-Build team’s workflow and eventual transformation.

Enter Design-Build, in which an architect and contractor bid on a project together, then orchestrate a project’s architectural drawings and construction somewhat simultaneously. The method ultimately reduces a construction project’s delivery timeline, which diminishes costs and maximizes profitability.

“You can think of [Design-Build] like a three-legged race,” Bickley said, “where the designer and the contractor can’t get to the finish line by themselves—they’re going to have to work together from the time they start.”

The efficiencies gained with Design-Build, however, require that all of its teams are maximally efficient with their workflows. But in 2014, the newly created, 12-person SCDOT Design-Build group’s workflow for reviewing and revising project documents before being sent to the field for construction was anything but maximally efficient.

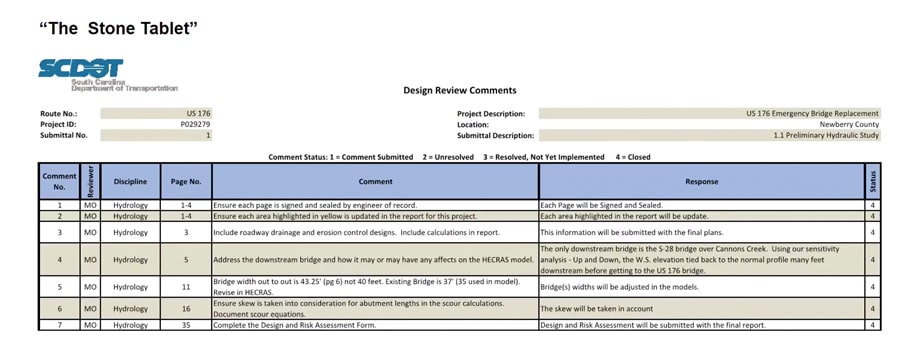

Without a dedicated software tool at the time to coordinate the design review process, the team was left with a manual, clunky workflow jokingly known as “The Stone Tablet” method—a reference to the primitive practice of carving words on a slab of rock. Under this process, a review coordinator would send out different comment forms to reviewers via email, at which point stakeholders would conduct their reviews individually before returning to the coordinator, who was now responsible for manually compiling all the comments, removing any duplicates and resolving conflicts.

This process was tedious and time-consuming, resulting in scheduling inefficiencies. “It was a painful process,” Bickley said. Among other points of confusion under this method, each comment had to indicate where on the page that comment was in reference to, creating miscommunication and potential for errors.

What’s more, if a reviewer didn’t respond or check in on a specific review, then the coordinator had to separately contact each party to get their feedback.

Finding Bluebeam

Bickley and a colleague were tasked with finding a new solution for the team’s painful design review process. Over the next several months, the team experimented with different considerations, including one featuring around 12 different spreadsheets with seven different tabs in each. “It sounded like a great idea at the time,” Bickley said, “but it was super overly complicated.”

The team then came across Bluebeam. However, as part of a government agency, Bickley said he wasn’t sure if it would be possible to adopt a new software tool to fix its design review problem. “If you’ve ever done anything with a government agency, it’s not a fast process,” Bickley said of the potential to get Bluebeam purchased, tested and implemented.

Somewhat surprisingly, Bickley and team didn’t have to make the case for Bluebeam. A member of the agency’s IT department, after learning of Bluebeam independently, emailed Bickley asking if his team wanted to give it a test. “After the 12 spreadsheet idea, we were ready for anything,” Bickley said. “We had looked at so many options, and Bluebeam was at the top of the list. We immediately realized it could have a huge impact.”

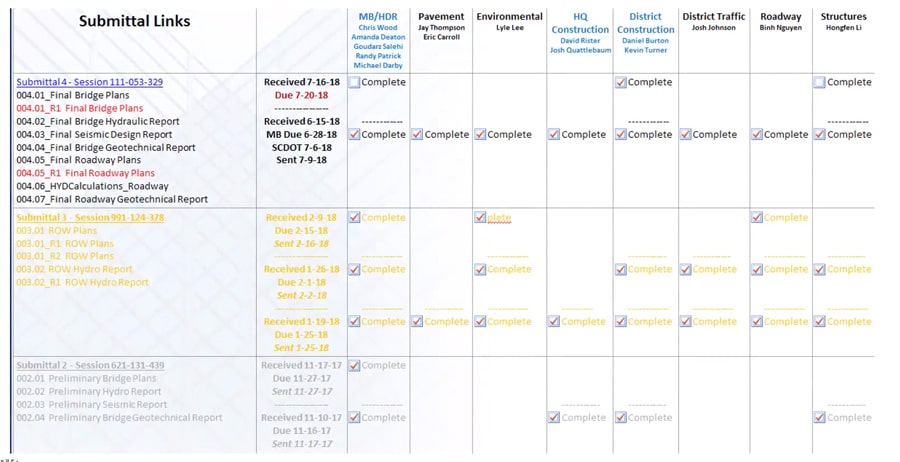

Bickley and team were instantly impressed with Bluebeam Revu, the software’s desktop solution for PDF markup and comment capability. But it wasn’t until they discovered Studio Sessions in Revu, which allows multiple users to collaborate in real time on a set of documents, that the team sensed the tool could be a game changer.

“Every one of our reviewers would be able to get in the single review Session at the same time,” Bickley said, “and that meant that everyone looks at the same set of documents and they’re able to make comments on those documents, not on a separate form, so the comments are also visible to the other reviewers.”

“It allowed them to collaborate at the very start of the review process,” Bickley continued, “and it completely eliminated the multiple comments and conflicting comments that we had in the past.”

What really sold the team on Studio Sessions was its ability, through custom statuses, to essentially automatically recreate a comment form that looked similar to the old “Stone Tablet” form the team was used to creating in the old workflow. “This [seeing the custom status option] was revolutionary,” Bickley said. “We hadn’t seen this in any online format, and we tried a lot of things.”

Making the Case

While it was almost instantly clear that Studio Sessions would completely transform the team’s design review process, what was less clear at the time was how it would transition its old, inefficient process to the new Bluebeam environment. Moreover, besides transitioning its established review documentation to Bluebeam, the Design-Build team would also need to train everyone to use a new tool and workflow, in addition to figuring out how to manage multiple reviews in Studio Sessions across several projects.

Prior to implementing Bluebeam, the SCDOT Design-Build group was already using Microsoft OneNote as a central location for all project information. Like Studio Sessions, OneNote is a tool everyone had access to that also allowed for real-time collaboration; it also allowed the team to create project-specific pages that would eventually include hyperlinks to corresponding project reviews in Studio Sessions.

OneNote was especially useful when the team created emails for Bluebeam notifications. “The big benefit was that multiple people can be in the file at the same time,” Bickley said, “making real-world, real-time updates.”

After putting in a lot of work to create and manage the new Studio Sessions-enabled review system, Bickley and team now had to present a pilot project to the agency’s leaders. To prepare, the team conducted an extensive, internal beta test of the new workflow, with the goal of trying to find weak links to correct and revise before embarking on the pilot project.

“We tried to break it,” Bickley said of the new Bluebeam-enabled workflow. “We created a few John Doe users and we tested it ourselves, and then we enlisted a few beta testers from the office. If there was a weak link in the system, we wanted to find it now, because it was going to be a disaster later on if we didn’t find those weak links.”

The team learned in its first beta test Session, for instance, that its custom statuses didn’t work properly—an additional step was needed to fix it. “Essentially, when we do the custom statuses, we needed to, in each document, open it up, make a comment, status it, save it,” Bickley said. “That was something that we had been doing for ourselves, but we didn’t realize that in a new Session with hundreds of documents, it would be something that needed to happen.”

When its beta testing was complete, the team wrote down its final “recipe,” as Bickley called the workflow’s official documentation. The team then used that process documentation to prove its case and, later on, help provide training when it was time for the larger Bluebeam implementation.

“It was really smooth sailing,” Bickley said of getting the design review process approved and in place on pilot projects, “because the process sold itself.”

The first official pilot project was a highway widening of I-77 in South Carolina, which was awarded to SCDOT in December 2015. “After several months of planning and work, we were really able to see if we could fly this plane,” Bickley said.

Simplifying Training

A large part of getting the pilot project up and running was training the project’s stakeholders on the new software and workflow. “Onboarding was going to be a daunting task,” Bickley said, “so we offered to provide it for both our SCDOT internal employees and staff, and the Design-Build team staff for this project.”

To streamline and simplify training, Bickley and team turned to a special tool: YouTube.

“We underestimated the amount of people we needed to train,” he said. “We quickly realised we needed a more efficient way to train, so we started with some Bluebeam Studio YouTube videos that we created.”

The team initially created two videos: one on how to create a Bluebeam account, and the other one as an overview of the new review process. Bickley said distributing these videos quickly became the best way to get information out at scale. “We would just send out the videos to the new users, and that left us responsible for troubleshooting instead of individual training,” he said.

Using the videos to proactively train while the team fielded troubleshooting ultimately helped it produce more training content. It took the most frequently asked questions, for example, and created a set of business rules for future users to reference. And as the I-77 project carried on, the team held a mix of in-person and online meetings with project stakeholders to gather feedback and identify new best practices.

“Getting everyone trained and comfortable took a lot of time,” Bickley said. “Eventually, we got it down so that enough people in the agency and the surrounding contractors and consultants—everybody had touched a lot of these design reviews … and a lot of the training happened in-house in their companies at that point.”

“Before you knew it, it was running by itself,” Bickley added.

Realised Results

In the eight years since first implementing Bluebeam Studio Sessions for its design review process, the SCDOT Design-Build team has had a lot of success. While it hasn’t quite been able to pinpoint quantitative measures of success, “the success is there and everybody sees it,” Bickley said.

Bickley is confident estimating that the new Bluebeam-enabled design review process has provided SCDOT “millions of dollars in savings.” “Our I-77 project was originally awarded for around $100 million, and using the previous ‘Stone Tablet’ method, it would’ve taken one person combining comments and organising the design reviews—it would have been a full-time job,” Bickley said.

“Design reviews [on the I-77 project] could have taken longer than 30 days in some cases. The general contract allowed for 15-day reviews, and no deadlines were missed, so this resulted in an average of 25% reduction in review times, compared to the ‘Stone Tablet.’”

Brooks Bickley,

SCDOT

The Design-Build group was able to award around $1.2 billion in the calendar year in its first year under the new system, with just one person able to coordinate reviews across all of its projects. In all, Bickley said Bluebeam has allowed the team to improve its productivity by 12 times.

“Design reviews [on the I-77 project] could have taken longer than 30 days in some cases,” Bickley said. “The general contract allowed for 15-day reviews, and no deadlines were missed, so this resulted in an average of 25% reduction in review times, compared to the ‘Stone Tablet.’”

The Design-Build group’s embrace of Bluebeam has been so successful that now the entire SCDOT uses the software.